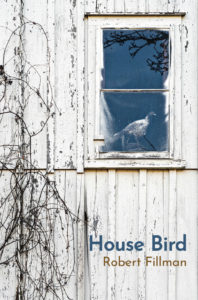

Robert Fillman’s debut collection House Bird is available for purchase at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Firefly Bookstore the publisher @Terrapin Books, and from other online retailers.

Back-cover Blurbs for November Weather Spell:

The poems in House Bird drill deep beneath the surface of domestic life, finding the essential truth in the tension between what gets said and what goes unsaid, exploring the consequences of speaking and the consequences of remaining silent. Fillman reveals how vulnerable we are, even in our own bedrooms, basements, driveways. Like in the Hopper and Wyeth paintings that inspire some of his poems, he finds the mood between desire and loneliness, that feeling so profound and universal that we can only bow our heads in recognition. A remarkable debut by a promising young poet. –Jim Daniels, author of Gun/Shy

These are wonderful poems, full of memory and keen observation, alive to their fingertips. I don’t think I’ll ever forget “The Blue Hour,” for instance, with its image of the dead ‘swirling / from chimneys like hundreds of souls / lured by stars,’ and then that final image of ‘Katie Estan’s older sister,’ dead from meningitis, who returns to drift past the speaker’s ‘snow-shackled rooftop.’ Poem after poem in House Bird is beyond beautiful. This is a book to savor, to reread. A splendid poetic achievement. –Jay Parini, author of New and Collected Poems: 1975-2015

Fillman excavates what might seem ordinary to find radiance. In striking, fully articulated poems, he explores generational ties and the pains-taking wages of parenthood. These poems are clear-eyed, generous, and compassionate. As when Fillman writes movingly about blessing a house for its future inhabitants, in similar fashion, these poems offer their blessings to readers. –Lee Upton, author of Bottle the Bottles the Bottles the Bottles: Poems

cover photo by Jason Martin

Reviews of House Bird

Sugar House Review: Review of House Bird by Jennifer Judge (full-text)

Newpages: Down Right Poetry – Review of House Bird by Ron Mohring (full-text)

Pembroke Magazine: Review of House Bird by Aaron Cole (full-text)

Good Reads review by Elizabeth Gauffreau (full-text)

The Pedestal: Review of House Bird by Brian Fanelli (full-text)

The Night Heron Barks: review of House Bird by Jon Riccio (full-text)

The Watershed Journal: Review of House Bird by Karen Weyant (full-text)

Excerpt from The Hollins Critic: Review of House Bird by George Franklin

The poems in House Bird are full of stories about families and neighborhoods, settings with which we are familiar and that make us feel comfortable. Fillman is homesteading a specific poetic territory, the house and neighborhood as a kind of liminal space. On one side of the threshold is the life we imagine for ourselves, full of possibilities, and on the other side is death: not a romanticized death or even a dramatic one, but a cold, empty negation that could engulf us at any second. There, in between, is the house where we grew up or the one where we raise our own children, a house built on the edge of contingency. House Bird explores a space few poets know exists.

The title poem of the collection, “House Bird,” is centered in this threshold space. The image is from Andrew Wyeth’s Bird in the House, a bird that the “evening light dislodged” “from its perch, shot it straight through / an open window, stone-gray / stopped on the mantel,” But, “House Bird” also describes the poet. (“House bird” is an old-time expression for someone who stays around the house.) In this case, it is the poet who takes the house as the place where our real lives happen, lives we have to work to understand. The light from the window seems to offer the house bird a kind of protection up there on the mantel. The “Starling in the Furnace Room,” who arrives in a later poem in the book, is not so lucky:

I remember feathers flying,

a tiny heart that ceased to beat,

the afternoon suddenly dark,

trapped in iridescent silence.

Fillman shows us how close death is and how we build our lives in relation to it.

The life the poet has built in this dangerous space has come at great cost. He never underestimates how hard it is to talk with other people, especially ones we love. In “Talking Over a Classic Rock FM Station,” he tells the story of drinking with his uncle, whose wife had told him “not to come back this time.” The uncle is drinking Old Milwaukee, and he is drinking cans of Coke. The “truck radio plays / one song after another.” Neither can say what needs to be said.

If the question is how we learn to live in this in-between world, the answer may lie in looking closely at the reality of it. I am reminded of Hardy’s line: “If a way to the Better there be, it exacts a full look at the Worst.” In what is one of the most striking poems in the collection, “The Snake Man’s Lesson,” Fillman describes watching a neighbor, Sid, “feed baby / mice to his saddle-brown boa.” When the audience of kids is frightened and hides their faces,

He promised it was over,

got us to uncover our eyes

in time to see that muscular

shiny body coiling around

its motionless prey. Years later,

I learned he was a professor

of wildlife management, who taught

us that death meant life, shed light on

the other side of the story

and dared us to look—

The trick played on the neighborhood kids, convincing them to open their eyes in time to see the white mouse crushed in snake’s coils is suspiciously familiar. It is the trick House Bird plays on its readers. For the brief space of the poems, we open our eyes just in time to see how close our lives are, not to a hypothetical death but to a death that is just outside the window or in the uncovered electrical outlet.

In House Bird’s final poem, “The Blue Hour,” Fillman finds his threshold space at dusk in autumn when the clocks are set back. The “extra blue hour of light” is a “sacred time when the living / and the dead can see each other.” He watches “the steam whirling / from chimneys like hundreds of souls / lured by stars…. Those souls are “caught between worlds / for less than a second, then gone. This was twenty years before he wrote the poem, and he ends it with another memory, a vision of “Katie Estan’s older sister,” who had died of meningitis, drifting past his “snow-shackled rooftop,” “a wobbling Venus, / dancing her way into the dark.”

The language of the poems in House Bird is elegant and clean. Anything else would sound false in Fillman’s personal landscape. The poems tend toward either free verse or syllabics. In other words, there is enough structure to get the job done, but not enough to permit us, his readers, the easy out of distancing ourselves from the poems, treating them as constructions rather than communications. Fillman has experiences he wants us to know about and to experience for ourselves, and he allows nothing to get in the way.

[from The Hollins Critic, Vol. LIX, No. 2, April 2022]

Interviews about House Bird

An Interview With The Poet Robert Fillman

Terrapin Interview Series: Meghan Sterling Interviews Robert Fillman